This is a great resource I posted to my Facebook Page for IWM. I am posting it here again in case you do not see my IWM Facebook page.

https://www.evms.edu/covid-19/medical_information_resources/#covidcare

This is a great resource I posted to my Facebook Page for IWM. I am posting it here again in case you do not see my IWM Facebook page.

https://www.evms.edu/covid-19/medical_information_resources/#covidcare

Lingo in the media are sometimes confusing or downright erroneous. This post tries to make the definitions clearer.

Case Fatality Rate (CFR) = (number of deaths) / (number of confirmed cases of the disease that have resolved)

The number of confirmed cases of the disease that have “resolved” means that we’re only counting those cases that have resulted in either recovery or death. Now there may still be people who are infected but have not yet recovered or not yet died. We’re not considering those in the denominator. Resolved cases means either the persons recovered or the persons died.

The difficulty with CFR is that the number of confirmed cases may not be accurately reflected. With a novel disease, it is difficult (especially in the beginning stages) to actually confirm a case due to the lack of testing and the lack of information regarding the characteristics of a pathogen. However, the CFR can help us understand the pathogen better, because scientists can look at data in a different way. Examples are (but not limited to): population by age groups; geographical locations; and other comorbidities.

Two other numbers (Infection Fatality Rate and Crude Mortality Rate) gives information about the risk of dying.

Infection Fatality Rate (IFR) describes the risk of dying if someone is infected. A population X is studied and the number of infections (V) within that population is counted. Out of those counted infections (V) of population X, F is the number of fatalities. Thus, the IFR for population X may be expressed as:

IFR = F / V

Crude Mortality Rate (CMR) is a number that describes the risk of dying relative to the entire population.

Crude Mortality Rate = (number of deaths) / (number of at-risk population)

Please take a few minutes to watch this video (below) by The Guardian. I, myself, was getting confused by all these “rates” until I slowed everything down and digested the video. I’ve read many articles and posts, and the video below is the best explanation with helpful animations.

References

I posted about two mask designs I’ve been working on. They’re actually located from the menu “CultivateNurtureGrow” on my IWM home page. Below are the quicklinks:

Enjoy!

If you haven’t seen our other article on PCR (polymerase chain reaction), you can find that here.

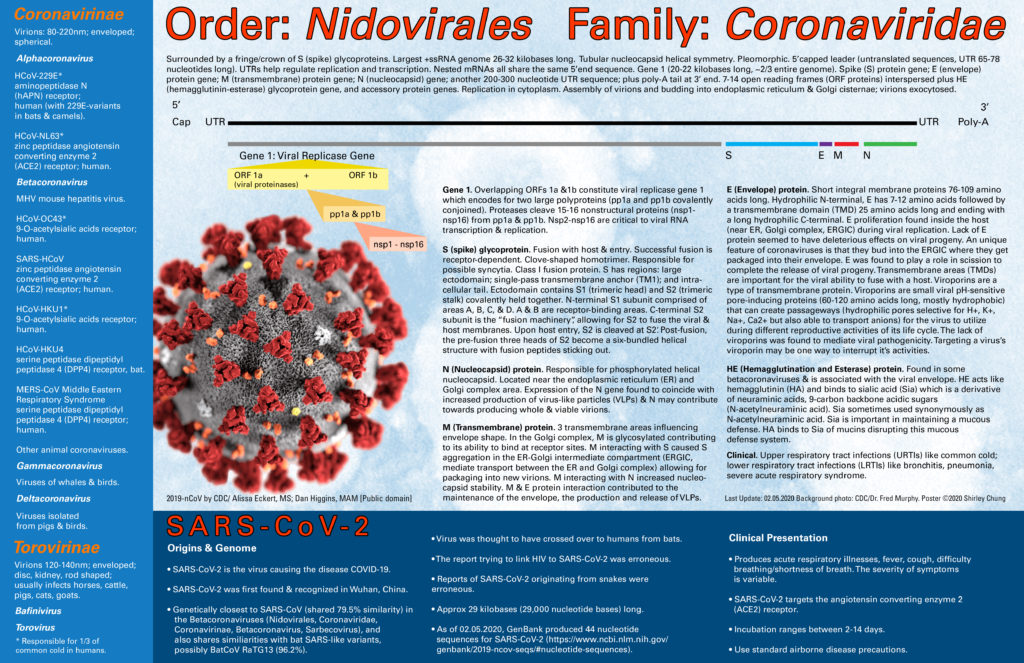

Download the high-quality poster here.

RT-PCR, Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction, is a variation on the original PCR whereby the template to be amplified is RNA (e.g. genomes of RNA viruses like HIV, HCV, Ebola, SARS, SARS-CoV-2). It is a very RNA-sensitive procedure–more sensitive than northern blot and RNase protection assay.

The Taq polymerase (used in PCR) from the heat-loving bacteria Thermus aquaticus cannot work with RNA directly. Primers are added and anneal to the RNA target if present. Reverse transcriptase (an enzyme that catalyzes the building of DNA from an RNA template) is used to form a complementary DNA strand (cDNA) transcribed from the template RNA. Reverse transcriptase works between 50-60 degrees C.

The cDNA (becomes our “new” template) is then subsequently used in the PCR process. It is important that the RNA strand be high-quality and of high purity. RNase H (ribonuclease H) is an endonuclease enzyme that cleaves RNA from an RNA-DNA substrate. RNase H usually has the job of removing RNA primers from Okazaki fragments during DNA replication. Reverse transcriptase has a RNase H function. As it builds the cDNA, it also compromises the integrity of the original RNA template strand. Note that RNase H treatment is not required before proceeding to PCR.

The solution is heated to 95 degrees C to separate the RNA from the cDNA. The temperature is then lowered to anneal the primers to the cDNA. The rest of the procedure follows PCR and it’s thermocycling process.

References

PCR stands for “polymerase chain reaction”. It was discovered in the 1983 by Kary Mullis. PCR is a technique that is used to create a whole bunch of copies (amplify) of a section of DNA or a gene for studying.

Download the high-quality poster here.

Ingredients:

Step 1. Denaturing. Heat to 94-96 degrees C. The heat will help break the hydrogen bonds thus separating the two strands of DNA. This takes 15-30 seconds.

Step 2. Annealing. Cool to 50-65 degrees C. This allows the primers to bind to the individual strands of DNA via hydrogen bonding. This takes 10-30 seconds.

Step 3. Extension. Heat to 72 degrees C. The T. aquaticus bacteria is a heat-lover which allows it to withstand and function at higher temperatures. Taq polymerase attaches to primers and then adds bases, one-at-a-time, from the 5′ to 3′. The approximate rate is 1000 DNA bases (1Kb, kilobase) per 1 minute.

References

The term “viral shedding” has been thrown around in the media coverage of SARS-CoV-2 or its better known disease, COVID-19. Let’s take a step back and explore what it means.

As the name suggests, “viral shedding” is formally defined as the release/expulsion of viral progeny (after reproduction) from the host.

On a microscopic scale, the host could be a cell, a bacterium, etc. On a macroscopic scale, the “host” would be the human/person would could literally “shed” viruses: through droplets when coughing/sneezing (airborne droplets or aerosol spread); other body fluids/secretions; urine/feces; or using their hand to touch something (contact spread).

A person who is displaying symptoms (i.e. symptomatic) can shed, but so can people who are not showing symptoms (i.e. asymptomatic). When we think about asymptomatic individuals: they may never have been infected before; they may be silent carriers; and they may have been sick and recovered (asymptomatic) but still able to transmit the pathogen. Asymptomatic shedding and spread depends on the characteristics of the pathogen.

This was originally a post on Integrative Wellness and Movement’s Facebook page, but so many people asked me that I’ve written a short summary with reference links here.

Hand hygiene is super important. Must have at LEAST 60% ALCOHOL to be effective.

Some chemicals used in hand sanitizers in the past have been found to be harmful and/or carcinogenic. The FDA has banned the use of these chemicals in hand sanitizers. Companies that make hand sanitizers have had to develop new formulations.

List of banned chemicals in the hand sanitizers are:

In addition, other chemicals for consideration were:

Directly quoted from “Safety and Effectiveness of Consumer Antiseptic Rubs; Topical Antimicrobial Drug Products for Over-the-Counter Human Use”:

(https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/04/12/2019-06791/safety-and-effectiveness-of-consumer-antiseptic-rubs-topical-antimicrobial-drug-products-for?fbclid=IwAR0PGwhIyCTj_epCJP8MuGpYrlL1c73diuEuJPj0fmqBXY7lZd0Jfv1G28A)

“In addition, in the 1994 TFM (59 FR 31402 at 31435) FDA proposed that the active ingredients fluorosalan, hexachlorophene, phenol (greater than 1.5 percent), and tribromsalan be classified as not GRAS/GRAE for the uses referred to in the 1994 TFM as antiseptic hand wash and healthcare personnel hand wash.”

References

Disclaimer. These are my own personal recommendations based on my knowledge, research, and personal experience. Interpret this information at your own risk. Recommendations and comments are also based on the accessibility of products for a pro-sumer consumer–something a knowledgeable person could buy (i.e. not just healthcare workers/government/military/etc.).

PPE’s stand for Personal Protective Equipment. PPE’s are whatever best protects you for the task you are doing at home or the job you are at. In terms of healthcare, PPE’s protect you and the clients/patients you serve. The number one most important thing is that “you go home safe”. You’re no good to anyone if you’re compromised.

This post focuses on PPE’s that may be helpful not only to healthcare students but the general public in response to the early SARS-COV-2 pandemic (COVID-19) at the current date of Feb 21, 2020. This article is not going to cover PPE’s regarding nuclear, chemical terrorism, bioterrorism, or any other kind of disastrous incident human-made or otherwise.

Disposable gloves are a staple. Get nonsterile nitrile powderless gloves. Gloves are rated by the thickness in millimeters (mils or mm). I like to get some in 3-4 mil and also have some 6-7 mil (textured) gloves around. Get some in black color because you can wear those in public (which I plan to do if the COVID-19 situation gets worse in USA). Some vinyl Grease Monkey gloves (I found them in Home Depot) are great to have as well. I like them looser for different tasks (like crafting and painting).

Picture A from https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B002EZQW7O/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_asin_title_o00_s00?ie=UTF8&psc=1

Sleeve guards are made of plastic or spunbond material. Plastic sleeve guards are rated by the thickness of the plastic in millimeters (mils or mm). Spunbond material may have a rating like AAMI (see gown section for explanation) or a company-specific rating (the company has their own rating system).

Picture B from https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00OU5L9ME/?coliid=I1HKV9VPLOUCLW&colid=3CYQKOF7GS4PE&psc=1&ref_=lv_ov_lig_dp_it

People don’t normally think of the eye as a potential route of infection. Think about it…it’s an open mucosal surface that can be compromised, penetrated, and infected.

Eye protection can get pretty detailed. We are not going to cover impact-resistant eyewear or any type of tactical or night-vision eyewear/eye protection.

In chemistry class, eyeglasses style protection won’t do you a lick of good in situations involving splashes/spills/aerosol sprays. Glasses do not form a seal around your eyeballs. So in the case of infection control, you’ll more likely need goggles style eyewear or eye/face shield that is incorporated with a hood (e.g. head-to-toe hazmat suits).

Goggles should be indirectly vented (venting system prevents outside particles from entering the interior of the goggle). Goggles should have a minimum rating of ANSI Z94.1/Z87.1+ Goggles should form a snug seal around your face. UVEX is my favorite brand. I’ve been using their eyewear for years including for skiing.

One additional note as I’ve received many compliments on my 3M Ratchet Headgear H8A, 82783-00000, with 3M Clear Polycarbonate Faceshield WP96. I’ve used these in wood shop and metal shop classes. I’ve also used these in gross anatomy and human dissection. They are awesome and worth the money. The ratchet system makes adjusting the headwear a breeze. These fit over a respirator (bayonet/cartridge style). I’ve used these for years and can highly recommend them for gross anatomy lab. Although they are an open-system (unsealed), they helped me survive formaldehyde fumes.

Picture C from https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B002A5DM3U/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_search_asin_title?ie=UTF8&psc=1

Researching for airborne pathogen protection, I’ve come across 3 rating systems and types of hoods. These hoods have an open face. If using a standardized AAMI (see gown section for explanation) rating, level 4 is the best (typically somewhat expensive). Assess your risk level. You may get away with AAMI level 3.

A popular spunbond nonwoven material is Dupont Tyvek (high density polyethylene fibers) which has a variety of uses including painting, autobody, and industrial chemical purposes. The highest rating I could find appropriate for infection control and biosafety was Dupont Tyvek 400 (also used for coveralls, booties, etc.).

Kimberly-Clark (KC) is a huge manufacturer of PPEs. KC’s Kleenguard A60 is rated for bloodborne and other pathogens. It was the highest level of biosafety protection I could find that was appropriate for COVID-19. KC also makes other disposable clothing like coveralls and suits with the Kleenguard A60 technology.

Picture D from https://www.rshughes.com/p/Kimberly-Clark-Kleenguard-A60-Blue-Universal-Microporous-Film-Chemical-Resistant-Hood-Full-Face-Opening-036000-45343/036000_45343/

Hair is like a great trap for microbes. There are beard covers to protect men’s facial hair, but those are seldomly rated (more like a facial shower cap). There are hair covers like surgeon caps or bouffant/scrub hats/caps. The caps also do not usually have a formal barrier rating. Assess your own personal risk. You may be better off clean-shaven.

Picture E from https://www.amazon.com/200-Pack-White-Beard-Mask-Mustache/dp/B07WPF4RBT/ref=sr_1_4?keywords=beard+medical&qid=1582548584&sr=8-4

You may be in a situation where you need disposable booties or shoe covers. If you’re going to use them, then make sure they are impervious–not the cheap ones that look as thin as a fabric softener paper that you throw into the dryer. Think about it…if you’re THAT worried that you need to buy them to use, your booties may very well be standing in a puddle of goodness-knows-what-kind-of-muck (e.g. blood, urine, vomitus, feces, etc.). A thin little thing will not hold up. You may as well just do without at that point. So make sure you buy booties/shoe covers that actually do the job. Better yet, get the kind that can come up above the ankles with enough extra for ties. That way you can form a good overlapping barrier between your “pants/coveralls” and the bootie.

I know it is a very “Asian” thing to take off shoes before going into the house. In a pandemic situation, assess your risk and please do take off your shoes before going into the house. This is especially applicable if you’re working in healthcare, labs, etc. I would buy a cheap boot-tray, leave it outside the house along with some disinfectant spray. Before going into the house, remove my shoes and spray them down. If you have a locker at work, that’s even better–keep your work shoes at work.

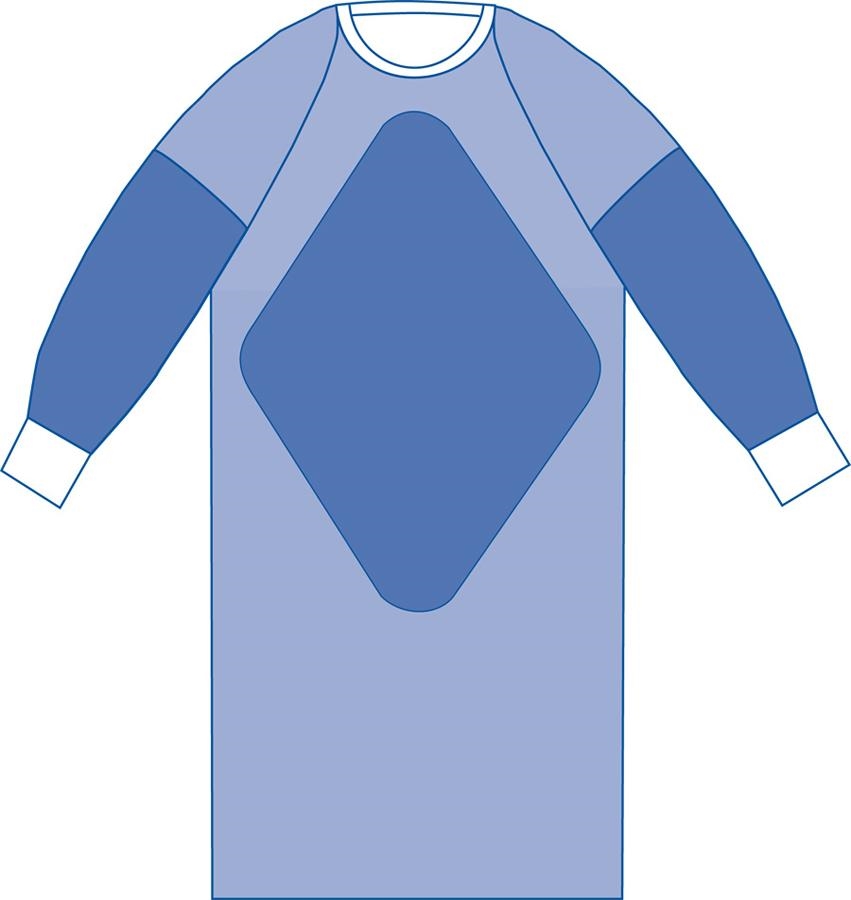

AAMI stands for the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation standard. AAMI has a rating system for gowns and surgical drapes describing their best use and also as a barrier against not only fluids/liquid spills/splashes but also liquid under pressure, blood, and pathogens. Level 1 is the lowest rating; Level 4 (impervious) is the highest.

Be sure to check the reference section below for detailed descriptions of PPE testing and ratings.

The critical zones are: the front (chest to knees) and sleeves; and wrist cuff to above the elbows.

AAMI Level 1. Lowest level of protection. Basic care. Minimal risk. Resists small amounts of light fluids. Light barrier.

AAMI Level 2. Low risk. Resistant to small amounts of fluid splatter and light soaking. Typical uses: blood draw; suturing.

AAMI Level 3. Moderate/medium risk. Barrier to larger amounts of fluid splatter/spray and soaking. Typical uses: arterial blood draw; IV; ER; trauma center.

AAMI Level 4. HIgh risk. Barrier and impervious to large amounts of fluid splatter/spray and soaking for up to 1 hour. MAY protect against viral penetration for up to 1 hour. Typical uses: surgery; blood borne pathogens; non-airborne infectious disesases.

I have found that AAMI Level 3 and Level 4 gowns would be appropriate for biosafety concerns. Level 4 gowns are very expensive. Level 3 gowns are still appropriate and affordable for buying in bulk, case of 100 gowns.

This is a great PDF presentation by the Minnesota Department of Health.

Picture F from https://www.devinemedical.com/SPT-2803CS-Sterile-Fabric-Reinforced-Aurora-p/spt-2803cs.htm?1=1&CartID=0

Masks should have the “NIOSH N95” designation. “NIOSH” stands for the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. N95 means that the mask is generally able to filter out at least 95% of small particles 0.3 microns in size. The theory is that airborne pathogens will “ride” on larger particles such as aerosolized droplets. N99 means the mask is generally able to filter out at least 99% of particles 0.3 microns in size. N100 means the mas is generally able to filter out at least 99.97% of particles 0.3 microns in size (meant to interpret as “effectively” 100%).

The alpha designation on masks are rated: “N” for not resistant to oil; “R” for somewhat resistant to oil; and “P” for strongly resistant to oil (essentially “proof”).

So, these are the variants (test yourself to see if you know what they mean): N95, N99, N100; R95, R99, R100; P95, P99, P100. See the pattern in the naming? Obviously, the better the mask, the more expensive they get.

With the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 still going strong, it’s near impossible for the average person (really anyone in any career field) to find and buy medical grade masks. I’m going with the “anything is better than nothing” principle. For myself, I make sure the mask has at least the “NIOSH N95” stamped on it. If it doesn’t, you’re basically holding a paper towel over your mouth and nose.

There are some really excellent resources in the “References” section. Please do check them out.

References

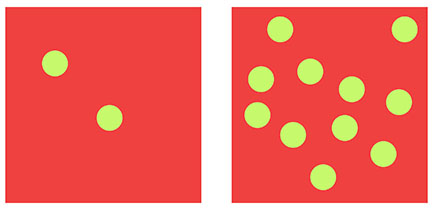

You may hear the term “viral load” referred to in a HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) education course, but term/concept may be more broadly applied to other types of viral infections including SARS-COV-2.

“Viral load” (VL) is a term used to describe the amount of virus (usually copies of virus or viral RNA) per unit volume. It is a measurement of concentration. Typically in medicine, VL refers to the number of viral copies per milliliter (mL) of blood.

Let’s think about some simplified examples. Let’s say there are 2 copies of virus-X in 1 mL of blood. That’s a LOW VL. It does NOT mean that there are no viruses in the blood; it just means a very low concentration. Another example, let’s say there are 10,000 copies of virus-X in 1 mL of blood. That is a considerably HIGHER VL.

The key to thinking about this is just because there is a low concentration of virus per unit volume of blood (i.e. low VL), it does NOT mean that there is NO virus there.

Why is this important? This is an important concept because many tests (including the test for HIV) have a concentration sensitivity level or range whereby the results of such a test are fairly accurate. If the VL is very low, the test for viral presence may not pick up the virus at all thus giving a false-negative.

VL may be very low and virtually undetectable if someone just contracted the virus (early stages of infection). In the case of HIV infection, antiretroviral protocol seeks to decrease the VL to such a low count that it is virtually undetectable.

Depending on the nature of the virus, knowing the incubation period would be helpful because one would want to test and retest the patient at the earliest possible opportune time, but also not too early.

References

Fletcher, J. (2018, November 29). HIV viral load: What it means, detection, and CD4 levels. Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323851#overview

SPECIAL MENU: Articles Index | Research Search Engines | References

Last Updated: 02.05.2020

For a high-resolution 300 ppi version download PDF here.

For a high-resolution 300 ppi version download JPG here.