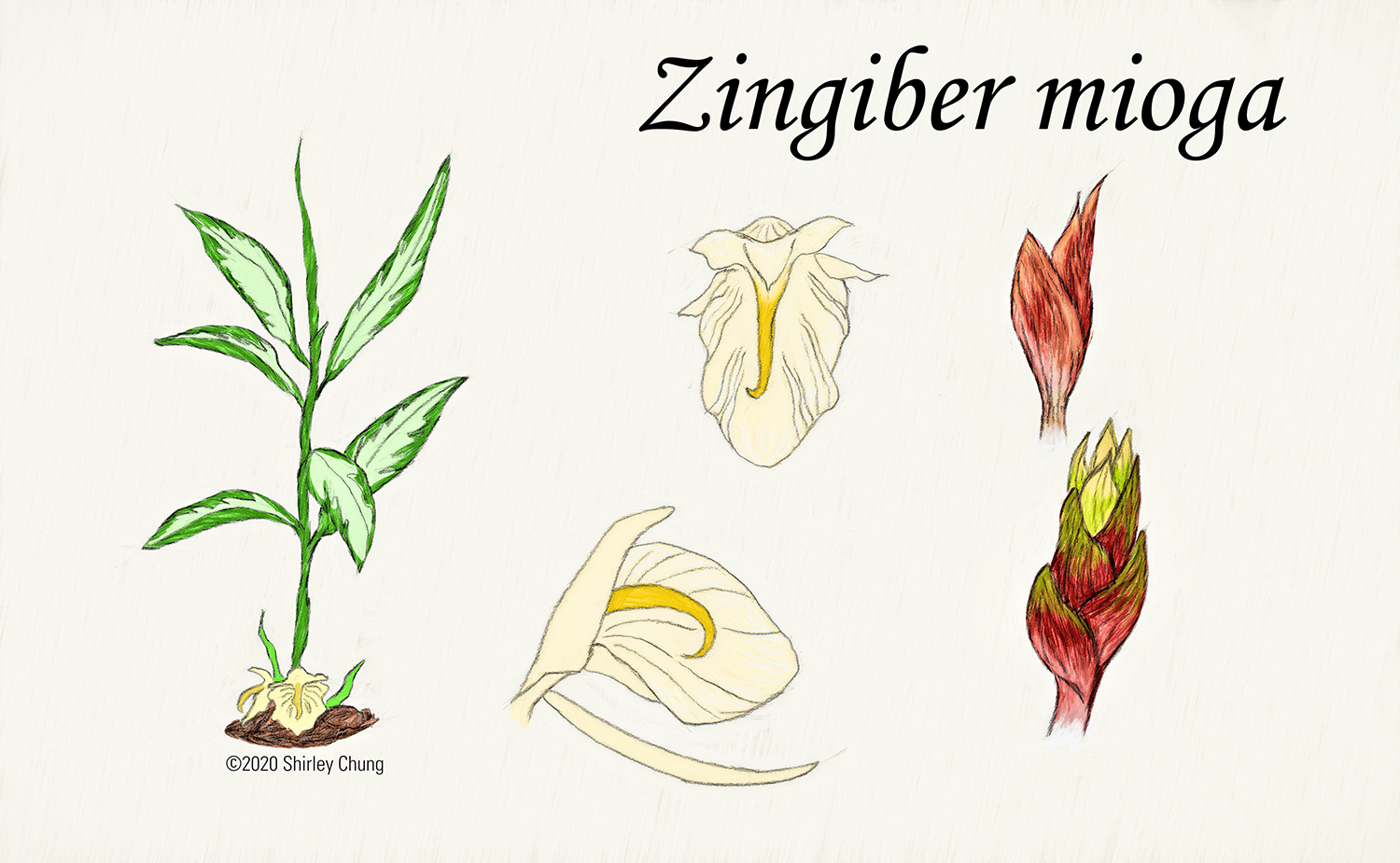

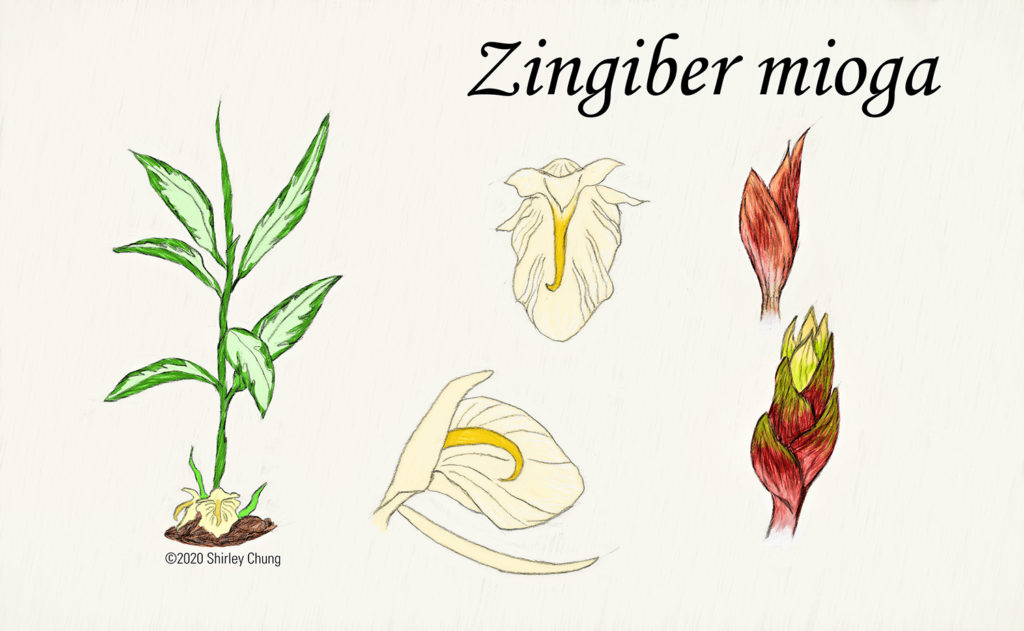

Zingiber mioga (“white arrow”, Japanese myoga)

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Zingiber mioga grows best in zones 8-11. This ornamental ginger produces orchid-like creamy yellow flowers near the ground and has glossy 3-foot stems and long green leaves streaked and edged white.

This is not the common ginger (Zingiber officinale) that is found in the grocery market and does not produce an edible root. Ginger is a perennial flowering rhizome (“rootstalk”) plant. Rhizomes are below ground (subterranean) plant stems that can send out roots and shoots from its node–typically extending horizontally, but also able to grow vertically.

Habitat/Growing Information.

Zingiber mioga is hardier than Zingiber officinale allowing Z. mioga to survive the Pacific Northwest weather and can be planted outdoors. It is reported to survive up to -10 degrees F. This plant likes moist soil and the morning sun and/or light shade. While it likes sun, make sure the light is filtered or indirect. New ginger plants require 1-3 yrs of uninterrupted/undisturbed growth before they will flower. If planting in a pot, make sure it is medium-deep and wide as this ginger spreads horizontally as well. Its orchid-like flowers bloom at the base of the plant.

Parts utilized.

The flowers (especially the buds) and shoots from Zingiber mioga may be cooked and eaten but its root is inedible. The unopened buds are somewhat of a delicacy (sometimes pickled), and the young shoots are commonly used in Japanese cuisine. Z. mioga has a milder flavor yet still distinctively “ginger”. The larger leaves may be used to wrap (and infuse flavor into) rice balls.

Properties.

The characteristic “pungent” flavor of this Z. mioga was identified as being comprised of 2-alkyl-3-methoxypyrazine, (E)-8-B-(17)-epoxylabd-12-ene-15, and 16-dial (miogadial, aframodial) (Abe et al., 2004). Miogadial is responsible for the flower buds’ flavor.

Z. mioga has historically been used: as anti-nausea; anti-migraine; anti-inflammation; anti-constipation; anti-diabetes; and other rheumatic and gastrointestinal maladies (Han, Lee, Kim, & Lee, 2015; Sharifi-Rad et al., 2017). Young flower buds and parts of the stem below ground (which contain zingerene, zingerone, shogaol, and B-phellandrene) have been used to attenuate menstrual issues, heart disease, and eye inflammation (Han et al., 2015).

Ginger oil extracted from the rhizome has active antimicrobial components a-zingiberene, ar-curcumene, b-bisabolene, and b-sesquiphellandrene (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2017). Gingerols are the main contributers from fresh rhizome; shogaols are the main contributors from dehydrated Z. mioga preparations (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2017). Due to the growing prevalence of drug-resistant microbials, scientists are trying to find more “natural” solutions (especially in food preservatives).

Z. mioga demonstrated antifungal effects on Candida albicans and Fusarium species (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2017). Ginger also demonstrated antibacterial effects on Pseudomona aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Salmonella typhi (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2017).

References

- https://www.seattletimes.com/life/tasty-ginger-can-look-good-in-the-garden-too/

- https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=ZIMI4

- https://www.southernliving.com/plants/ginger

- https://www.rhs.org.uk/Plants/134575/Zingiber-mioga/Details

- https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/151801-Zingiber-mioga

- https://www.gardeningknowhow.com/ornamental/flowers/ornamental-ginger/ornamental-ginger-plant-varieties.htm

- https://www.gbif.org/species/2757086

- https://www.gardenclinic.com.au/how-to-grow-article/know-your-gingers

- https://homeguides.sfgate.com/ginger-plants-not-flower-71955.html

- https://www.theflowerexpert.com/content/aboutflowers/exoticflowers/gingers

- http://tropical.theferns.info/viewtropical.php?id=Zingiber+mioga

- https://www.flower-db.com/en//flower:1242

- https://www.uniprot.org/taxonomy/136225

- Abe, M., Ozawa, Y., Uda, Y., Yamada, F., Morimitsu, Y., Nakamura, Y., & Osawa, T. (2004). Antimicrobial activities of diterpene dialdehydes, constituents from myoga (Zingiber mioga Roscoe), and their quantitative analysis. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry, 68(7), 1601-1604.

- Han, J., Lee, S., Kim, H., & Lee, C. (2015). MS-Based Metabolite Profiling of aboveground and root components of Zingiber mioga and officinale. Molecules, 20(9), 16170-16185.

- Sharifi-Rad, M., Varoni, E. M., Salehi, B., Sharifi-Rad, J., Matthews, K. R., Ayatollahi, S. A., … & Sharifi-Rad, M. (2017). Plants of the Genus Zingiber as Source of Antimicrobial Agents: from Tradition to Pharmacy.